A few months ago, I was asked to speak at a niece’s wedding, on behalf of my family. The Master of Ceremony, a young man in his mid-thirties, dynamic, vibrant and fluent in speech, said it was now the turn of a representative of the bride’s family to say a word. As I strode up to the podium, he asked the audience to put their hands together for one of Cameroon’s most renowned writers, Mr. Martin Kenjo wan Jumbam. As the applause rose from the hall, the young man talked about the books he said I had written, citing particularly The White Man of God, which he said he had read in his secondary school days, and how much he had enjoyed reading it.

Mistaken identity

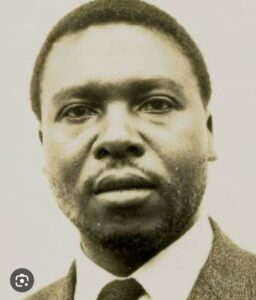

I took the microphone from him and began by thanking him for his thorough knowledge of The White Man of God, The White Man of Cattle, and Lukong and the Leopard, the three books authored by Jumbam. Then I told him much as I enjoyed the sustained applause and the adulation of the crowd, I had to admit, like John the Baptiser, that I was not who he said, or thought, I was. The authorship honour of those books, I told the confused young man, had to go to Kenjo Jumbam, my elder brother, who is no longer with us, but in whose shadow I feel honoured to walk.

There and then, I tossed aside the script I had written full of advice on what the young couple could do to live happily thereafter. I then decided to talk to them about building bridges of goodness. I told them that my brother Kenjo had built solid bridges of goodness in the form of the books he left behind, and which a whole generation of Cameroonians had studied with much delight, as was evident from the young man’s knowledge of the works. I and the other family members have been basking in the warmth of the legacy he left behind and crossing that bridge of goodness with much pride.

Another case of mistaken identity

I told them it was not the first time that I was being mistaken for my brother. In fact, a few months earlier, I had gone to a police station in Douala to certify a document. I had a copy of the document onto which the relevant stamps had been affixed at the government treasury but I had somehow forgotten to take the original document along with me. The secretary who received me – very politely, I must say, and to my greatest surprise, since they are always very rude in those offices – reminded me that I needed to bring the original document before the copy could be validly certified.

I said she was right, thanked her for being so kind and was about to walk out when she called me back. “The Commissioner is in his office. He is your brother (meaning, an Anglophone) and may be he will sign it for you.” I said I would try my luck and gave a timid knock on the door. After a moment of silence, a booming voice answered from inside, asking me to come in. I walked in and behind a huge table sat a well-built, neatly shaven man in his mid forties, with a receding forehead, and a pair of horn-rimmed glasses neatly perching on the tip of his nose. His face was buried in that morning’s edition of Cameroon Tribune, the government daily paper, which he seemed to be reading over his glasses. In a country where appointments and dismissals are announced through the government-controlled media, unpleasant surprises sometimes await those who fail to keep up with the news. It is not rare for a government functionary to come to work in the morning just to be told that they no longer have access to what was yesterday their office, as a new occupant was already waiting in the wings to take it over.

He kept me standing for a minute or so, long enough for me to feel who was really in charge. Then without lifting his eyes from the paper he asked me in French what I wanted. When the response came in English, he sat upright, scrutinized my face for a few seconds, then putting the paper aside, he asked me to take a seat. He took the document from my hand and his eyes seemed to brighten up when he saw my name.

“Oh, are you the writer of The White Man of God?” he asked, a smile dancing around his lips.

“No, that was my brother, Kenjo.”

“Oh, I see. That’s a great book. It was in our literature programme at the Seat of Wisdom College in Fontem, and really enjoyed it. Where is he today?”

I told him he passed on several years ago and he expressed his sympathy. He then started telling me what he could remember of the story while at the same time reaching for the two or three stamps on the stamp stand. He affixed them onto the document, all the while talking about the characters in the book, saying how much I had made him recall a beautiful book he would very much love to read again. We spent a few more minutes together and before I left, he gave me one of his business cards, and asked me to call him, if I needed more help. We have since become good friends, all because my brother had built good bridges through his writings, which I continue to cross to this day.

Several years after my brother’s death, the bridges of goodness he left behind still serve me and my family members well. Had he left behind him a legacy of bad memories of the extortion of the weak in an unbridled quest for riches, a practice that is so prevalent in our Cameroonian society today, those deeds would still be haunting us to this day.

“Be kind and generous to people you meet wherever you may be,” I told the young couple. “Such acts of kindness and generosity will always serve as the mortar holding together the blocks of this bridge of goodness that will long outlive you; and that your children, their own children, and your other family members will always bless you for, long after you are no longer here.”

Douala, July 22, 2016