By Douglas A. Achingale*

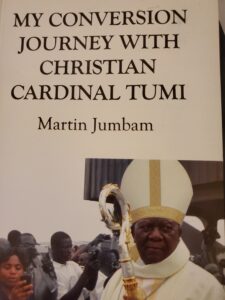

It is often said of well-crafted books that they are usually so enthralling that it would be hard for the reader to drop them until they get to the final word. This observation, to my mind, most conveniently suits Martin Jumbam’s My Conversion Journey with Christian Cardinal Tumi. For, this work of Christian literature, a collection of 16 breath-taking articles and two electrifying interviews, spread over 161 pages, explores the ‘growth’ of the author – from an aficionado of worldly pleasures to a practical believer whose entire being is now animated by the Word of God! Amongst a few other related subjects, of course.

The icing on the cake is the flavour-filled language in which Jumbam’s lines are so bewitchingly couched. Read them; you will find yourself soaring with the author in such literary altitudes that would make landing a difficult pill to swallow, when it finally happens.

Having either been first published in Cameroon Panorama or l’Effort camerounais or not, the articles and interviews are divided into four parts, viz: “The Journey Begins”, “My Prayer Life Firms Up”, “My Interest In Church Governance Grows”, and “The Social Dimension Of My Faith”.

Getting renewed in the Faith

Martin Jumbam begins his “journey” with an article titled “I marched with Christian Cardinal Tumi”. In it, he recounts his participation in a five-hour march for peace around the city of Douala organized by the Emeritus Archbishop of the Douala Archdiocese, on 1 January 1993. The author, a secular freelance journalist, had as main purpose to cover the event for a media organ.

That was his very first encounter with Christian Cardinal Tumi. In the preface to the book, Jumbam enthuses: “Little did I know that the Lord was leading me to him that he may in turn lead me back to the Lord.”

As it were, the march was characterized by prayer recitals and singing of religious songs, most of whose wordings and lyrics the deviant Christian (Jumbam) was unfamiliar with. Hear the effect of the march on him: “Five hours and nearly 30 kilometres later…I had stared so long and so deep into my Christian life, or what was left of it, that I took a firm decision to run back for shelter under the canopy of Mother Church…”

An early fruit of this decision was a resolve to spend some time of rest and meditation in the monastery in Mbengwi, beginning 1 August 1993. Jumbam’s godly experiences during his stay here constitute the bulk of the content of his second article entitled, “I spent a week with the Cistercian monks in Mbengwi”.

Those seven days clearly served to further his journey to conversion, just as he had expected. The expertly counsel he received from the monks and priests in the monastery, the utter quietude of the place, and the long hours of prayer and meditation brought Jumbam much closer to the Lord than ever before.

While there, he went for confession and received the Holy Communion for the first time in over 30 years! The ensuing relief was glaringly overwhelming. In fact, Jumbam left the Mbengwi monastery an exhilaratingly pensive and transformed man. This is how he captures his feelings when he quit the place: “…I left Mbengwi steeped in prayers. I felt like a newly minted coin.”

Communing with a Saint

Having rushed back to embrace his Creator, it went without saying that Martin Jumbam could not miss being amongst the multitude to welcome Pope (now Saint) John Paul II to Cameroon, when he came visiting for the second time in September 1995. Indeed everything about the Sovereign Pontiff’s visit to Yaoundé, as reported in “I walked beside a Saint”, enchanted the author. Of particular interest is the emphasis Jumbam lays on the Pope’s sharing of the Catholic clergy’s anguish over the feeling of insecurity “engendered by senseless violence that has been unleashed on them for reasons no one seems able, or willing, to explain.”

On that occasion the Supreme Pontiff “cited the case of Monsignor Yves Plumey, the Emeritus Archbishop of Garoua, assassinated under circumstances that have so far remained a mystery.” What baffled Jumbam, and certainly other observers, was the direct manner in which the Pope confronted “the head of the Cameroonian nation over the question of insecurity, which not only threatens the clergy but the ordinary people as well.”

Animated by God’s spirit

The writer’s spiritual growth had now become evident in every action or activity he found himself involved in. And this is undoubtedly the case to this day. That is why he records in “Come, follow me” that not only is he a founding member of the Catholic Men’s Association (CMA) of the Our Lady of Annunciation Parish in Bonamoussadi – Douala where he worships, he is also called upon to have spiritual reflections with the group, such as the one he did on July 24, 2007. It was based on three words from the Sacred Scripture – “Come, follow me” — that constitute the title of the article in question.

Sometime later, the author was on the campus of the University of Buea where he had an appointment with a colleague, so he says in “A prayer at the University of Buea”. It was a Saturday and UB stood “unbelievably empty and quiet.” Having arrived earlier than the meeting time, he was virtually alone on the campus for most of the time he was there. He immediately saw the presence of God through the teeming elements of nature that adorn the campus and which he viewed with rapture. The silence of the place was so “prayerfully inviting” that the renewed Christian could not help reaching into his pocket for his rosary.

After Christian Cardinal Tumi had led Jumbam back to Christ, the former remained a close collaborator of the man of God’s in the Archdiocese of Douala. In “The Catholic Church and the radio”, Jumbam, amongst other things, recounts his involvement in the running of the diocesan radio, Radio Veritas, as well as his tenure as General Manager of the diocesan printing press, MACACOS, from 2004 to 2008.

The counselling dimension of the writer’s transformation comes out clearly in “Train seminarians to be good managers of human and financial resources” where he has some overly useful advice for priests, including the need for them to be grounded in responsible human and financial resources management. In “Father, watch your health!”, the writer equally counsels priests to take good care of their health by watching their meals, for “It is virtually important that our priests remain in good physical health to attend to the spiritual needs of the people God entrusted to their care.”

A show of gratitude to those who have touched one’s life in a special way is one of the hallmarks of a true Christian. That is what Martin Jumbam does to the Emeritus Archbishop of Bamenda, Paul Verdzekov, “now in heaven”, to Prof. Bernard Fonlon, his teacher, and to Prof. Daniel Lantum, the architect of Jumbam’s acquisition of a scholarship to do post-graduate studies in Spain and of his actual departure from Cameroon.

The two interviews in this volume are those which Jumbam had with Rev. Fr. Zephyrinus Mbuh, SD, a liturgical expert of the Diocese of Kumbo, and Laura Anyola Tufon, head of the Bamenda Archdiocesan Justice and Peace Commission and member of the National Commission on Human Rights and Freedoms. The one dwells extensively on the need for some rituals during Mass to not be over-protracted, and the other on the successes registered by the Justice and Peace Commission in the area of conflict management in the North West region.

From the foregoing, there is no question that by recounting the progress of his journey to conversion, Jumbam is literally holding the hands of other ‘lost’ Christians in a bid to lead them to the Lord as well. His extensive use of biblical quotes and references, quotes from Saint Augustine’s book, “Confessions”, and others seems to be meant to get straying Christians steeped in the Lord’s word as well.

Autobiographical thread, palatable style

All of which literature is fastened with a thread of autobiography that visibly runs through the length and breadth of the work. Jumbam’s articles present vivid and memorable snapshots of his early childhood as well as his school-going days at home and abroad. The impression one has upon perusing “My Conversion Journey…” is not that one is reading a collection of articles and interviews but rather that one is watching an illuminating movie, with the subtitled sections into which the articles are divided appearing like episodes in the film.

Of course, the writer’s perspicuous rendition and journalistic style make for easy understanding. His plenteous use of highly evocative imagery gives the effect of his words being chewed delectably with hugely palatable condiments. The more you turn the pages, the greater the appetite to voraciously devour the luscious lines.

*Douglas A. Achingale is a social worker, writer and researcher in the literatures at the University of Yaounde 1.