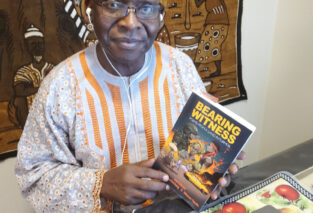

Thumbing through Martin Jumbam’s MY CONVERSION JOURNEY WITH CHRISTIAN CARDINAL TUMI (2015) brings to the Catholic mind and to any avid reader THE CONFESSIONS OF SAINT AUGUSTINE for this that the parallels are shouting: autobiographical of sorts, spiritual development, meditations, social commentary and the role of a moral colossus (Cardinal Tumi) in his conversion journey!

In simple, refreshing, elegant, vivid and captivating prose the author takes us through his conversion journey in the light of Christ’s “come, follow me!” When Christian Cardinal Tumi paid out his net through “The March of Peace” in Douala in 1993 little did he know that he would catch a fish in the person of Jumbam!! From there on Jumbam has not looked back as witnessed in his book: a dynamic and committed Catholic Christian.

Every spiritual journey begins with a step and the first steps as a kid, were in his native Nkar, precisely at Gharu, where he came into contact with Catholicism through reverend gentlemen who somewhat intrigued him by their mannerisms.

In every spiritual journey you need somebody to lead you through. Jumbam found this in the person of Cardinal Tumi. In every spiritual journey there are coincidences; at Gharu he loved the company of the late Joseph Ngalim who begat Reverend Father George Tomrila Ngalim whose ordination ceremony somewhat fired something in him!

In every spiritual journey, silence, prayer, meditation, canticles, mass and confession are primordial. Jumbam had a foretaste of these at the Cistercian Monastery in Mbengwi! Every spiritual journey is strewn with events that uplift the mind and the soul: Jumbam covered, as a journalist, the second visit of Pope John Paul II to Cameroon in 1995 where the pontiff promulgated the Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation, Ecclesia in Africa!

When Jumbam describes his days in Nkar I cannot but think about my family! My late father, one of the first orphans at the Shisong Orphanage, grew up in Nkar in late Joseph Ngalim’s family compound in Gharu. They were, in all intents and purposes, brothers; this relation has spilled over to their respective siblings! I still have fond memories of my holidays in Gharu!

Prayer, they say, is talking to or conversing with God! From being unable to recite The Hail Mary or The Lord’s Prayer in the early days of his conversion (during the March for Peace in Douala), Jumbam firms up his prayer life with a prayer, remarkable in its spontaneity, cadence and poignant poetic prose, at the University of Buea campus. The lines, powerful in their simplicity, are reminiscent of Leopold Sedar Senghor’s Ode to the Black Woman!

Any committed and dynamic Christian must have an interest in church governance. Professor Bernard Fonlon held tight to this view a long time ago. In fact, during the creation of the major seminary in Bambui, he was of the opinion (which prevailed) that our priests should not be formed like the curés de champagne but should be steeped in scholarship so as to face the ever increasing challenges of a changing world. Jumbam makes the case for priests to be formed in human resource and financial management. Apparently, this did not go down well with certain clerics but when a roll call is made of financial scandals in certain parishes and church institutions then Jumbam’s is worth its weight in gold.

Jumbam highlights his encounter with a church luminary, the late Archbishop Paul Verdzekov (Father Paul). When he died, the now emeritus Bishop of Obala, His Lordship Jerome Owono Mimboe lamented the loss of the finest of brains in the Cameroon Episcopal Council. Jumbam brushes a similar portrait and goes further to extol his faith, bilingualism and courage in an authoritarian environment. As editor of Cameroon Panorama, he was a fiery critic of any form of dictatorship. At the height of the Bishop Ndongmo treason trial, he was the head of a Catholic Bishop delegation that met and discussed with the late Ahmadou Ahidjo. Other personalities like late Professor Bernard Fonlon and notably Fai Woo Bastos Professor Daniel Noni Lantum (to whom he pays tribute for ‘holding up the torchlight to guide his steps’).

The author throws light on the social teachings of the church. He highlights the ‘devastating consequences of abortion’; how the church practices justice and peace through the Justice and Peace Commissions and how these commissions have contributed in settling conflicts in Cameroon as well as his crusade for the donation of blood prompted in large measure by the death of an only sister.