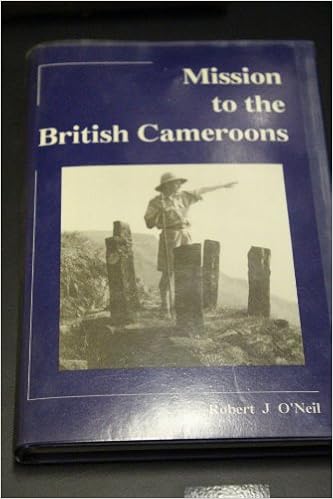

Mission to the British Cameroons (Mission Book Service, St Joseph College, 1991) is a book on the missionary activities of the Mill Hill priests and sisters in the British Cameroons authored by American-born, Mill Hill missionary Father Robert J. O’Neil. It was published in 1991 when the Catholic Church that is in Cameroon was celebrating its centenary. It is prefaced by Archbishop Paul Verdzekov of Bamenda who salutes it as an “opportune” and “indeed providential” work, which will benefit and inspire “present and future generations of Cameroonian Christians”.

This 185-page, 7-chapter book opens with a bird’s eye-view of the historical evolution of Catholicism in the British Cameroons, from the days of the German Pallotines Fathers, to the brief sojourn of French Sacred Heart missionaries under Monsignor Plissonneau, who took over after the German expulsion from the Cameroons after World War 1. It then zeroes in on the Mill Hill Society’s activities proper. It acknowledges the great contribution of the German missionaries who, although in Cameroon for only a short time, succeeded to plant “seeds [of evangelization] of very high and resistant quality” (p. 6).

Influential Bishop Rogan

Three Mill Hill bishops served in the British Cameroons : Monsignor Campling, who was recalled from Uganda where he was serving as a priest, was here for only a few years (1922-25). His successor, Monsignor Peter Rogan, another Uganda veteran, put in well over 30 years (1925-62). A man of wit and humour, Bishop Rogan was a poet of sorts who used his writing skills to raise funds abroad for the local church.

His over 30 years in the Cameroons saw an incredible expansion of the Catholic school system under Father Simon Staats, a man who was “unexcelled in his knowledge of education matters in the Cameroons” (p. 65). Many Cameroonians today will no doubt agree with Archbishop Paul Verdzekov that “whatever we are, we owe it to Mill Hill” (p.140).

Change or Drown

Monsignor Jules Peeters, Bishop Peter Rogan’s successor as Bishop of Buea (1962-72), nicknamed the “daring builder”, quickly realized that the Mill Hill Society either had to “face a slow death or go along with the times and renew” (p. 139). The numerous schools and colleges the Mill Hill Society set up throughout the British Cameroons were already churning out high quality Cameroonian clergy and elite, including two bishops, Paul Verdzekov of Bamenda and Pius Awa of Buea.

It therefore looked for a while as if the Mill Hill Society would render “its own existence [in Cameroon ] superfluous” by resisting change. Fortunately, however, it took Bishop Peeters’ warning to “change with the times or drown” seriously. Not only has it still remained firmly established in English-speaking Cameroon, it has also stretched its roots into the French-speaking parts as well.

Pictures of Priests and Catechists

English-speaking Cameroonians of a certain generation, especially Mill Hill products, will find this book a treasure trove to read and re-read. Not only does it give the names and biographies of numerous priests, who were known and largely cherished by them, it also contains interesting pictures of some of those priests of old (Nabben, Schmid, Onderwater, Jacobs, Olislagers, among others).

In fact, Dr. Bernard Fonlon, of glorious memory, would no doubt have been very delighted with the cover picture of Father Thomas Burke Kennedy in Laikom, stretching out his hand to the sky as if to indicate the limit of his missionary activity. Dr. Fonlon, who had been so powerfully influenced and inspired by Father Kennedy, sang his appreciation in beautiful poetic renditions.

Early Cameroonian Christians, especially catechists (Epie, Effen, Maimo, etc.), those real pioneers of evangelization in this country, have also been remembered in both words and pictures.

This book is indeed the work of a historian. One senses that obsession with archival references, endnotes, footnotes and careful documentation of interviews and eye-witness report. Its greatest merit seems to me to lie in the simplicity of its style and diction. In fact, the language does not call attention to itself at all: hardly any high-sounding words and expressions. In the end, the tribute to the activities of the Mill Hill Fathers in Cameroon seems to me to be so memorable because it is couched in such simple language.