Being Catholic: Dr. Bernard Nsokika Fonlon’s Greatest Achievement

By Lambert Mbom

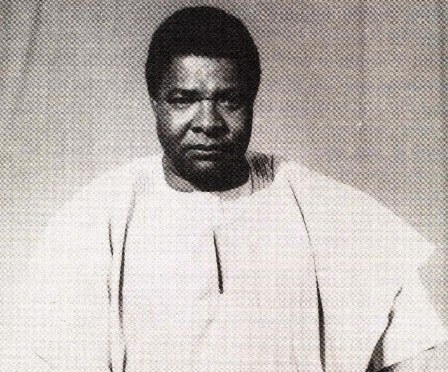

August 26, 2025, marked the 39th anniversary of the untimely passing ofone of Cameroon’s finest sons: Dr Bernard Nsokika Fonlon. A lot has been written about Fonlon. This larger-than-life distinguished man of letters left his mark and continues to be celebrated even now. Fonlon’s legacy lives on. This year, I would like to highlight one oft-neglected fact of Fonlon’s life, namely, being Catholic. It is often treated as a footnote in the entire drama of his life. I dare say that of all the major accomplishments this Cameroonian patriot registered, and there are many – genuine intellectual, wise African, and genteel politician – the one Fonlon would have celebrated the most is the fact that he was a Catholic. What would Fonlon have been if he had not been Catholic? He could be the great intellectual, the savvy politician, “professeur agrégé” not simply because he was a genius, and what an egghead (I first learnt this word from Fonlon) he was, but precisely because of his faith as a Catholic. This defined and colored his life. Formed in the crucible of Catholic faith, the seminary, Fonlon remained a Catholic throughout his life.

Being Catholic is often taken for granted, especially by a prevalent, dominant secular culture. While some praise the Catholic Church for its role in development, think of education, healthcare, and social programs, others fault it for its bastardization of cultures, especially African culture. To be Catholic, it would seem, one must convert, so to speak, to Europeanism. I have often wondered whether the more appropriate thing is to describe one as a Catholic African, otherwise said a Catholic who happens to be African, or an African who happens to be Catholic. Without being polemical, if there is no East nor West in Christ, then there is no African nor European in Christ. Catholic becomes a noun and not an adjective, or may be simply an adjectival noun. Christianity, by some historical accident, arrived on the shores of Africa clothed in European garb. And that is no small historical accident, merely parenthetical, may be. One might go on a limb to say Fonlon would have taken issue with Fr. Jean Marc Ela’s book: My Faith as an African, not so much for its content as for the title. And yes, I am being polemical. And what is more, since grace builds on nature and nature interplays with nurture, being a Nso man was not merely incidental and tangential to Fonlon’s Catholicity. Yet, his Catholicism shone in and through his “Nso-ness.”

Catholicism infected Fonlon and permeated every fiber of his being. His faith informed his life, both intellectual and political. There is no argument that Bernard was a genius. One of the greatest marks of his remains, the skillful deployment of his mastery of philosophy, which he transported to, or rather integrated into, Literature. He would belong to the hall of fame for philosophers and also in Literature. Even though he owes his education to the Catholic Church, his gifted brain, his natural aptitude provided the launchpad for the excellence in scholarship. You could endow a chair in philosophy in his honor and another in the humanities, too. Hope you see the drift! He had a very “Catholic” mind. His faith permeated every fabric of his life. He was not a Catholic only on Sundays. Not a Catholic in Church. The words of John Mbiti that the African man is notoriously religious could be paraphrased to say Bernard Nsokika Fonlon was notoriously Catholic, in that from Baptism to death, whether in public or in private, Catholicism permeated his whole being, not just much of it, but in fact all of it.

Fonlon stands as a shining example that could help in unraveling a peculiar conundrum of our time, namely: can one be authentically African and authentically Catholic? This proposition needs to be teased out more. I wonder whether Fonlon slaughtered a goat at the death of his father and later on the passing of his beloved mother, as Nso custom requires. One thing is clear: He had a grasp of Nso culture. Culture as the basis for worship demanded an adequate knowledge of the traditions of his people. The twin dangers of syncretism on the one hand and outright dismissal of the culture of his people on the other are horns of a dilemma he skillfully navigated. Being Catholic makes it or should make a difference in one’s life. His creation of the journal ABBIA and the Department of Comparative African Literatures in the University of Yaounde is testimony of his respect for the cultures and traditions of Nso, Cameroon, and Africa. Yet, this did not conflict with his faith as a Catholic. He lived out what Pope Benedict XVI expressed so beautifully: “Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction.”

Fonlon stood tall in two areas where some Catholics are struggling, namely as a university professor and as a politician. As a professor, truth and excellence guided him. Of the many issues university professors in Cameroon score very low marks in one that is jarring is the politicization of academia. They have become political hacks and quacks. One of the greatest tragedies of academia is its capitulation to politics. The so-called intelligentsia have become a mere shadow, lacking any spine. If gold can rust…the commercialization and sexification of academic degrees is a conversation for a different day. Are there any Catholic professors in universities in Cameroon? It is not apparent. After all, Cameroon is a secular state and so why the hullabaloo about being Catholic? For Fonlon, it made the difference.

Even in politics, Fonlon brought his Catholic social ethics to bear. I wonder what Fonlon would have done ahead of the forthcoming elections? Yes, one can be Catholic and a good politician. Sadly, the cream of Cameroon’s politicians are products of Catholic schools and other denominational schools. The fact that Cameroon is in a political cesspool today begs the question of what the Catholic politicians are doing. Fonlon serves as an example of putting faith at the service of the government. What values are they living by, if any? Clearly, they have been swallowed up not just by the enticing secular humanism but in fact by atheistic humanism. Being Catholic for them is the icing on the cake if at all. It is the opportunistic fanfare meant to whitewash their true devious identities.

Today, I would like to touch on an aspect of Fonlon’s life which has hardly been given enough consideration, namely, Fonlon, the chaste celibate. There are many questions I would have loved to ask Fonlon. One of them would have been why he remained a chaste celibate all his life. How he remained one in spite of the many opportunities. Obviously, years of seminary formation prepared him for the requisite chastity in the celibate state intrinsic to the Catholic priesthood. He had come too far that abandoning this now would be anathema according to him. He had Scripture to back him: When the hand is put to the plough, nobody who looks back is worthy of the kingdom. Hence, having lived through seminary formation in anticipation of the priestly life, not becoming a priest did not deter or dispense him from this lifestyle. Bernard already had an orientation towards this lifestyle and felt an imperative to live it on. This was undoubtedly counterintuitive, especially within the context of a culture where a man without a son is considered a curse. Fonlon chose to serve God as a layman in a chaste celibate state. He consecrated his life, informally albeit, and offered his virginity for the sake of the kingdom. His fecundity came through his years as a professor, “birthing children intellectually and also through his written works, and like Christ said, some are incapable of marriage because they were born so; some, because they were made so by others; some, because they have renounced marriage for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. Whoever can accept this ought to accept it. Mtt.19:12. And so, Fonlon accepted the challenge to renounce marriage for the sake of the kingdom. Fonlon lived out the evangelical counsels of poverty and chastity freely. Our contemporary world laughed and mocked him as a “mugu.” A man of such accomplishments who would have attracted and had whatever quality of woman he wanted and would have amassed such wealth, instead chose poverty and chastity in a celibate state.

In the Church’s theology, only women can be consecrated virgins. Christ is the groom, and so within the spousal economy, the virgin who consecrates herself becomes the bride. In a sense, the Church holds that only women can be brides and hence only women can be consecrated virgins. Fonlon, however, dedicated his life as a selfless sacrifice to Christ. In a highly sexualized world in which sex runs amok, Fonlon’s life stands as an example. The testimony of the life of a man like Fonlon gives credence to the fact that high-profile men can live chaste, celibate lives. Here is a layman with the benefit of seminary formation whose commitment to celibacy is an example to our priests and religious.

The sacramentality of Bernard Fonlon’s entire life, premised on his faith in Jesus Christ, is the point. Fonlon would agree that “What we love, we shall grow to resemble.” He loved Christ, so he grew to resemble him. Fonlon became an outward sign of inward grace.

In his book, “What is the point of being a Christian,” Timothy Radcliffe, former Master of the Order of Preachers, also known as the Dominicans, writes, “The point of any religion is to point us to God who is the point of everything.” Fonlon’s life pointed to God, and reading about him, especially within context, one can only assume it is God’s doing. Quoting Cardinal Suhard, Archbishop of Paris in the 1940s, who wrote: To be a witness does not consist in engaging in propaganda not even in stirring people up, but in being a living mystery. It means to live in such a way that one’s life would make no sense if God did not exist.” Cardinal Radcliffe concludes: There should be something about Christians that puzzles people and makes them wonder what is at the heart of our lives. Fonlon’s life incarnated this reality.