(Revised and reproduced from Cameroon Panorama Nos. 376 of April 1993; pp. 17-19) and 377 of May 1993; pp. 18-21).

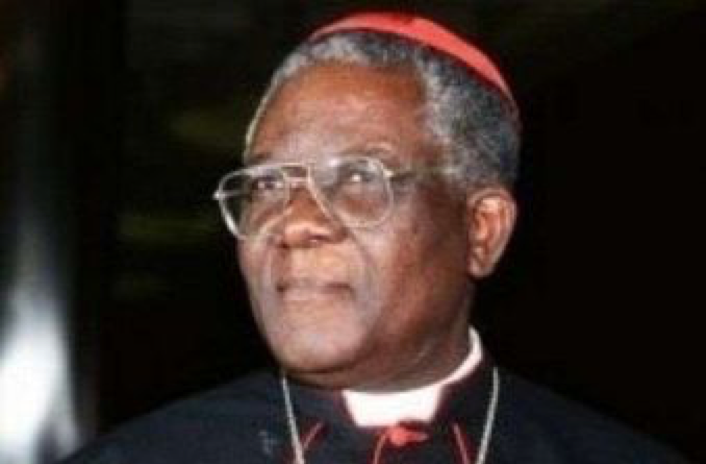

The news of the “March for Peace”, which His Eminence Christian Cardinal Tumi was organising was in the air all week long, but the details were rather sketchy. That is why I was not sure of what to expect as I approached the large crowd in front of the small Saint John’s Parish Church in Deido, Douala, at 7 o’clock on the morning of January 1, 1993.

No placards?

What struck me as I scanned the crowd for a face to pin a name on, was the absence of placards and banners. I had thought that I would find an excited, noisy crowd waving a forest of banners and placards, bearing high-sounding slogans, calling on the powers-that-be to restore to our land and people the peace that once was theirs. But, what I saw surprised me: just simple, ordinary people, mainly women of a certain age, many of them dressed in white or in deep blue uniforms, lining up behind a crucifix, singing songs of praise to the Lord and telling the beads of their rosaries.

I was still wondering what to make of it all, when I saw Doctor Arnold Yongbang a few feet away. With Doctor Yongbang there, I began to breathe a little easier as I knew I would have answers to some of the questions I had on my mind. A few days earlier, I had stopped by his house, as I so often do whenever I need reliable information on just about anything happening in the land, to get details on the impending march, but he hadn’t been more enlightened on it than I was, not having seen nor talked with the Cardinal that past week.

The Cardinal’s ring

‘You’ve answered present then, eh?’, Doctor Yongbang asked as we shook hands with each other. ‘Couldn’t miss this for anything in the world’, I remember answering him. We were still wondering about the itinerary of the march when we saw the tall figure of the Cardinal towering above a small crowd a few feet away. That was the first time I had ever come that close to His Eminence, and I wouldn’t have known how to greet him had Doctor Yongbang not immediately gone up to him, taken his hand in his and kissed the ring on it, genuflecting in the process. That was new to me; so I, too, took His Eminence’s hand in mine, brought his ringed-finger to my lips, genuflecting as I had seen Dr. Yongbang do. The action was so fast that I didn’t have the time to take a closer look at that ring as I would have loved to.

Bishop Awa’s ring

Just then, my mind raced back in time to the day I met Monsignor Pius Awa of Buea in his cousin, Mr. Peter Akumchi’s house in Yaounde some seven years or so earlier. That was the first time I came face-to-face with such a high-ranking official of the Catholic Church. I remember approaching him with a mixture of awe and uncertainty but, to my greatest surprise, delight and relief, Monsignor Awa suddenly said something unbelievably funny, and before I knew it, I was already at ease with him, asking him questions that have always intrigued me about the Catholic Church, and getting frank and direct answers wrapped in a seemingly inexhaustible fount of down-to-earth humour I hadn’t imagined a prince of the church could be endowed with.

When I had to leave, I noticed that Bishop Awa, who had taken off the ring from his finger for a while, quickly put it back on before offering me his hand. I remember hesitating for a second, not knowing what to do, and then deciding just to shake it. Now I know I should have kissed his ring and perhaps knelt down for his blessing. That was what his Lordship probably expected me to do as well. Don’t we learn everyday!

Call off the march

As we greeted the Cardinal that morning, that usual, broad, warm, reassuringly contagious smile opened up on his face as he jokingly said: ‘Weti wuna di do here, you pagan people dem?’ Then, casting his eyes from that commanding height of his over the crowd that was growing by the minute, he said: ‘I hope no one shows up here in a party uniform or with a party banner’. We also echoed the same hope. Then he added: ‘The government has been very scared of this march and has sent delegation after delegation to me to call if off’. That was news to me and I asked why.

‘Well, that is because they don’t believe that a gathering of this nature at this time can be devoid of politics.’ Then he added with that disarming smile of his: ‘But, I told them this march had nothing to do with their politics. This is a purely religious event and I won’t call it off.’

I recall someone near me wondering aloud if that was the reason the place was, in his word “swarming” with CENER (secret police) agents. To prove his point, he pointed to one fellow loitering around the corner and to another one pretending to be repairing a motorbike a few feet away, but who kept shooting furtive glances at us. He also showed us another suspicious group of three or four individuals lurking at another corner who he also identified as plain-clothes men, claiming he knew their type well and that they were up to no good. I don’t know how the Cardinal would have reacted to that claim, but he didn’t hear it, busy as he was greeting those who came up to him.

Many would die for Maria

Just then a beautifully decorated pick-up truck drove into the mission yard, bearing the statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary. His Eminence looked at the crowd milling about the yard and remarked, with a smile on his face: ‘There are many people in this country who would not hesitate to lay down their lives for Maria.’

Then the pick-up truck swung round and began slowly to move out of the yard. The Cardinal with one or two of his priests and some altar boys, took their places behind it, and we fell in line a few yards behind them. As we came out onto the street, I was surprised to see that the head of the procession was nowhere in sight. I also looked behind me and the crowd in the churchyard seemed to have grown tenfold.

I had no rosary!

A woman next to me intoned a song in a language I guessed was Ewondo. This was followed by much hand clapping and dancing. After that song, another woman began to recite the rosary. I saw just about everyone with a rosary in hand and it suddenly dawned on me that I might be the only one there without one. For a few minutes, I felt at a loss, wondering whether I really belonged with that crowd of believers at all. What intensified that feeling of loss and guilt was the sudden realisation that I couldn’t even recite a single prayer in French correctly; neither the ‘Hail Mary’, nor the Lord’s Prayer. I then decided that I would say the prayers in English instead. There, too, I stumbled on one or two words and gave up the exercise. What of Lamnso, my native tongue? There, I had better luck, but my mind kept straying to the French prayers around me.

I was still wondering how best to immerse myself in the prayers when Gregory Alem, a CRTV journalist on FM 105, walked up to me. I asked him in a whisper if he was on duty, and he said he was there to join the march, having decided that he could no longer stay on the sidelines while others were doing so much to shape the history of our land. That was why he was determined, he said, to join the Cardinal’s march for peace.

The Cardinal was already nearly a kilometre ahead of me although when we started off, I was only a few yards behind him. As we went along, more and more people were joining the procession and preferring to be as close to the Cardinal and the statue of the Virgin Mary as possible. It was not long before Gregory and I were far apart from each other.

Fallen by the wayside

All around me, prayers and songs rose and fell as groups sent their praise and admiration to the Lord. I realised to my horror that I could neither recognise nor join in any of those songs or prayers. It then began to dawn on me that I had indeed fallen by the wayside in my religious life. Not that I hadn’t been aware of it, though; but it was how far away I had fallen from the right path that hit me with such frightening suddenness.

Unable to join the chorus around me, I decided I would withdraw into myself and try to come to grips with my relationship with God since such an opportunity to stare into the rear-view mirror of my life uninterrupted for hours on end, had never presented itself to me before. As we wound our way at a snail’s pace through tiny, pothole-laden streets, from Deido through Bepanda Voirie to Ndokoti and well beyond, I suddenly felt how the dregs of all those years of neglect of my Christian life had hardened and were weighing down so heavily on the shoulders of my conscience.

Here I am, Lord!

The only other time I felt an outsider in church was on April 22, 1992 in the Cathedral in Bamenda during the ordination of five young men into the sacred priesthood. Maika, my wife, Mrs. Rita Bomki Akumchi, her cousin, and I had travelled from Douala the Saturday before to be present at that ceremony to witness one of ours, George Tomrila Ngalim, take his place among the clergy of this nation.

George has always been like a younger brother to me, just as I had been like one to his father, the late Joseph Ngalim, a simple man who had lived a simple, honest life of a great Catholic Christian.

As I stood there watching George, I felt really sad that his father couldn’t be there with us to see his first son take the vow of the priesthood. In fact, I fought back a tear when George answered the Lord’s call, and his mother, accompanied by his junior brother, Stephen, standing in for his father, led him by the hand to the altar to surrender him to His Grace Archbishop Paul Verdzekov, as their own gift to the Almighty Father.

I remember His Grace Archbishop Verdzekov’s commanding voice exhorting his fellow priests to abide by the dictates of their vocation. If you cannot stand the smoke, he told them, get out of the kitchen. That was one of the most profound sermons I have ever listened to. The power of that message seemed to be amplified by the magnificence of the music, which the conducting priest, Reverend Father William Neba, standing on a raised platform, seemed to be literally pulling out of the belly of the cathedral with his arms. Music of rare beauty and intensity. Heart-lifting sounds, which I still sometimes hear, in my mind’s ear, whenever I take a momentary respite from the rat race. It brought tears to my eyes.

The river of age

On that day, my mind was not so much on George – even though it was his day – as it was on his father, whom the Lord had called ‘home’ some years ago. I recalled that in August of 1984 when I returned home after several years abroad, one of the first things my old mother asked of me, was to go down to Gharu, Joseph Ngalim’s compound, to greet him for, she said, he had been very ill and would be pleased to see me.

My family has always considered me Joseph Ngalim’s ‘son’ because of the liking he had taken for me from the time I was only a child. I must have been only five or six years old when he, still a young primary school pupil, asked my parents to allow me to stay with him in a hut he had, like all young men of his age, built for himself in his parent’s compound of Gharu, a kilometre or so away from our compound at Mboon.

I still have fond memories of those childhood days when I would play in the yard with other children of his compound while watching out for him. When he came back home, I would run up to him and he would always give me something to eat, usually a piece of meat from the day’s hunt, or a fruit.

My friends and I would sometimes play by the banks of River Mensai that takes its rise from the Ngongba hills that brood so menacingly above. River Mensai, today a mere shadow of its former self, used to rush down the hills into the valley, seeming to us who had never seen any other bigger river, frighteningly massive, as it wound and unwound itself down the valley like a huge wounded snake. We were always warned against playing too close to it as it was said to be unforgiving to anyone who was foolish enough to fall into it.

Thinking of those days, over thirty years later, on that bright, sunny day in August of 1984, was like taking a ride up the river of age to those days of unblemished innocence.

Out of touch

As I walked down the hill leading to his house, I wondered what I would say to him. Whenever I was home on vacation, my mother would always ask me to go to Tobin and visit him and his family. He was always very happy to see me and took a keen interest in my academic progress. Unfortunately, as my quest for the ‘Golden Fleece’ took me further and further into the beckoning, wide world, I lost touch with him.

So, it was with a very heavy heart and guilt feelings that I walked into his house that sunny August afternoon. As I took his hand in mine, a smile walked its way across his agony-wrinkled face. He could hardly turn his head as his neck hurt him so badly. I recall fighting hard to halt a lump that was already crawling unrelentingly up to my throat, always a prelude to a flood of tears, which I could already feel warm on my cheeks.

I remember apologising profusely for my protracted silence over the years. In his usual manner, he merely smiled and said he had been wondering if he had done me wrong, but that all that was now history as he was happy I had thought of him immediately I returned home. It was then that the tears came tumbling from my eyes, a bucket-full. I was to let another generous flood of tears wash my face some months later when I learnt of his death. He had apparently recovered and gone back to work when the illness struck again, and he succumbed to it. I was in Yaounde, trying to find a job and feed a family, and couldn’t unfortunately attend his funeral. I did, however, pray that the Lord receive him with trumpet blasts.

August 29, the day to remember

Meanwhile, the Cardinal-led procession continued its slow, dignified and graceful journey through the streets of the nation’s economic capital. I came out of my reverie only long enough to notice how far we had gone, and then I was back in my shell again.

I remember that a few years ago, on a dreary, rainy and foggy morning of August 29, I stood over Joseph Ngalim’s grave in the small cemetery below the Church in my village of Nkar. August 29 is a memorable day to my family, being the day my father-in-law, Pa Anthony Tala, a long-time teacher of the Catholic School in Nkar, died. On that dreary morning, my wife and I joined the other members of the family to call on the Lord to accept Pa Anthony Tala, our father and His humble servant, among His chosen flock. Afterward, I walked over to Joseph Ngalim’s grave and communed for a while with one of the greatest souls that ever lived on earth. George, then a deacon, was also present.

My beloved ones

Beside my father-in-law and Joseph Ngalim, many a loved one of mine also reposes in that small church cemetery. Monica Bongberi, my only sister, lies a few feet away. She had given up the struggle against a merciless ailment and had passed away right in front of my eyes some ten years earlier. I remember that even though she died in my presence, I only felt the impact of her absence one year later when I went back home on vacation. I remember standing above her compound, waiting in vain for those shouts of welcome and warm hugs and smiles of joy, which I was so used to. I stood there staring into space, tears abundantly washing my face, to the surprise of many. May the Lord Almighty place His soothing hand on Monica’s forehead!

Not far from Monica, lies Gertrude, my sister-in-law. Our phone rang one summer Sunday morning in Edmonton, Canada. I picked it up and an emotion-drenched voice told me that Gertrude was no longer with us. When the impact of that reality finally hit home, I jumped up, screaming and refusing to believe what I had just been told. Her husband, Kenjo, my brother, had left Laval in Quebec, where he had been studying, only a few days before, and hadn’t even had the time to call to inform us of his safe arrival in Cameroon, when we learnt of his wife’s death.

Maika, a regular church-goer, nearly pulled me by the hand to church that Sunday morning to pray for the repose of Gertrude’s soul. ‘Even if the devil has truly made his home in your heart’, I remember her telling me as I grudgingly trudged behind her, ‘at least, on a day like this, you should ask the Lord to forgive your sister-in-law her sins and welcome her into His kingdom’. I knew she was right, although I didn’t want to seem too eager to agree with her. I did, however, follow her to church to ask God to welcome Gertrude among His chosen few.

John, my boyhood friend.

A few feet away, under a fresh mound of earth, lies one of my childhood friends, John Fondzeyuf. John and I had served our first Mass as altar boys together way back then. I remember shocking my mother by waking up too early to go to church that day. John and I had been selected the previous day to serve our first Mass that morning, and had been warned not to be late. Despite my mother’s threats to tan my skin if I didn’t go back to bed immediately, I left for church, arriving when it was still very dark and, to my surprise, John was already there, dressed and waiting. You could have heard our heart-beats a mile away as we later accompanied the priest to the altar under the close and critical scrutiny of the elder altar boys, our trembling backs to the congregation.

I still find it difficult to believe that John is no longer with us. I hadn’t been able to attend his funeral, but the impact of his death had hit me a few months later when I went to greet his family in Yaounde. I walked in and was greeted by John’s picture staring at me from the wall. I sat down on one of the all-too-familiar chairs, talking to Aloysia, his wife, and it was just as it had always been. It even looked as if John would walk out of the room any time to join us. I could still hear his voice, in my mind’s ear, as usual noisily contesting my claim to a traditional title, calling me, albeit jokingly, an impostor. We would then engage in friendly gibes at each other for hours on end. As those memories made their way back to mind, I felt tears welling up in my eyes, and it was with some difficulty that I held them back from his children. May the Lord give John a huge pat of welcome on the back!

In that small cemetery, lie people who have been precious to me. Hopefully, when my own time runs out, my mortal remains, too, will join those of my loved ones at one corner of that cemetery. My soul, God willing, will link hands with all my family members who have slept in the Lord to give praise and thanks to God Almighty for eternity.

Peace with myself

Those were the thoughts that were winding their way through my mind at the same snail’s pace as we went through the streets of Douala. Never before that day did I realise how much I needed to incise my past as a way of coming to full grips with my present life of a fallen Christian. Thereafter, I suddenly felt at peace with myself. I still, however, felt inadequate before the Lord. I couldn’t remember the last time I ever spent more than a few minutes in church. I would, more often than not, drive my family to the church door, drop them there, only coming back for them when I knew the Mass was over. I had always found spending an hour in church unbearably boring, and I was wondering if I would stand the Cardinal’s Mass that was to follow the march.

Peace on earth

However, no sooner had the Cardinal arrived than he was at the altar saying Mass. I remember Gregory Alem and I earlier expressing the fear that, at his age, the Cardinal might not stand the tempo of such a long march; but there he was, still looking strong and preaching peace on earth to men and women of good will.

As I listened to him, he seemed to be talking to me personally. The peace he talked of seemed to be making a home in my mind and in my heart. Since then, I cannot say that I have suddenly become an ideal Christian, but at least I do now feel the urge to lead my family, not only to the church door, but right into the church itself. There, I listen without the urge to glance at my watch. The message of the Gospel has been tickling my heart these days more than at any other time of my life. Even though I will never open my mouth in church to sing for fear of offending whoever may be standing near me, I have always had a weakness for church music which, over the past few months, has been sounding even more splendid than ever before.

God bless the clergy

The Cardinal’s march for peace seems to have done me much good. Only the other day, not only did I listen with unusual attention to, but was also profoundly moved by Archbishop Verdzekov’s pastoral letter denouncing torture in our land. I remember bowing my head and asking God to bless the Archbishop and the victims of torture in our land. However, I still haven’t found the courage to pray for those who order or execute torture, as the Archbishop recommends. How can one ever do that? I wonder.

Not long ago, though, I would never have thought that God could listen to someone like me, and the idea of praying for no less an eminence than an archbishop could never have occurred to me. Maybe the indescribable satisfaction I felt after that prayer is a good indication that the Lord did, after all, listen to His humble servant!

It seems by marching with Christian Cardinal Tumi for peace in our land, I had found that much desired but elusive peace with myself. A prayer for the Cardinal. May he too remember my family and me in his prayers.