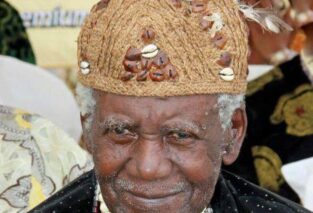

“Are we praying to Father Paul, or for Father Paul?” Christian Cardinal Tumi, the Emeritus Archbishop of Douala, wondered as he paid his friend, Father Paul Verdzekov, his last tribute on February 13, 2010. As days blend into weeks, and weeks into months, and soon months into a year since Father Paul Verdzekov, the Emeritus Archbishop of Bamenda, left us unexpectedly, I too wonder with Cardinal Tumi whether to pray to him or for him.

As days go by, a persistent feeling of something undone continues to gnaw my entrails. Since Father Paul left us, I have not been able to pay him a tribute, in my own way, as many have done. And I know that the more I try to ignore this feeling, the deeper it will continue to grow and cloud my mind. This is a strange feeling, given that I was not particularly close to Father Paul. In fact, I only came to meet him fairly often after Christian Cardinal Tumi entrusted the management of the Catholic printing press, MACACOS; to me from 2004 till I stepped down in 2008. This period also largely coincided with the years of Father Paul’s retirement from the head of the Archdiocese of Bamenda when he came to rest in Douala more frequently than before.

First encounter

Sometime back in 1969, the government transferred the Federal Bilingual Grammar School from its original site at Man O’War Bay, some five miles west of the coastal town of Victoria, to its present location in Molyko, Buea. I was in Form 5 and preparing to write the London General Certificate of Education ‘O’ Level. My mind was entirely focused on this exam and no where near anything religious.

That is why I was not too keen when my childhood friend, Emmanuel Konglim, today with his Maker, came to tell me, a broad smile spanning his face, that he had met a young Nso priest in Buea. His name was Reverend Paul Verdzekov. That name didn’t ring a bell in my mind and I merely shrugged my shoulders in total indifference.

Unlike Emmanuel, an exuberant, out-going individual, who was always much at ease around people of a certain class in Church or in civil life, I am rather shy and happy when I can pass anywhere unnoticed. Emmanuel was always at the forefront of encounters and took a boyish delight in giving details of his encounter with people, be they in the ruling circles of the Church or in political and academic circles. “One thing you’d really like with Father Paul Verdzekov,” he said, pulling out a copy of a magazine from his bag, “is this: Cameroon Panorama. He’s the Editor-in-Chief.”

Emmanuel knew how excited I always was when it came to reading newspapers and magazines. In fact, one of my classmates, today a corporate lawyer in Obama’s land, once accused me of succeeding in my exams through the use of magic. His reasoning was that while others were busy studying, I was, more often than not, to be seen reading newspapers and magazines in the library. But when it came to time for tests or exams, I always did well. Therefore, he concluded, I could only be using magic. His views did come as a shock to me, but not enough to discourage me from first heading for the newspaper section whenever I went to the library, which was often. Emmanuel knew my weakness for the press, especially as I was also on the editorial team of a slim school publication that didn’t survive the school censorship for too long.

Attack on tyranny

As soon as I laid my hand on the copy of the Cameroon Panorama that Emmanuel had given me, I immediately browsed through the editorial. I was struck by the robust and virulent attack on the elections that had just taken place in the Bokassa-created-and-ruled Central African Empire. Under the pen-name “Barah Mbiybe”, Father Paul openly denounced what he called the “election buffoonery” in that unfortunate Central African country. That was the first time I saw the word “buffoonery” and I immediately rushed for my dictionary, nodding my head in admiration.

Those were days when Ahmadou Ahidjo ruled Cameroon with a heavy-fisted, “blood-and-iron” conviction. Under no circumstance did he take kindly to any views that might smack of even slight criticism of his rule, or that of a fellow dictator, especially one in his backyard, like Bokassa or Mobutu. We all trembled for Father Paul as we read his open denunciation of African rulers who trampled afoot the basic rights of their people. It was easy to see the fist-punches Father Paul was sending also landing firmly on Ahidjo’s own ribs. We knew it would be a miracle for the censors, seasoned on intolerance and press bashing, not to reveal their fangs to the young priest, sooner rather than later.

When I expressed my admiration for the magazine, Emmanuel smiled and said he knew I would like him. He then announced that Father Paul was coming to say Mass at our school. I looked at him as if he’d just lost his mind. Our school was a government school and I couldn’t see the school authorities authorizing a Catholic priest to say Mass on campus. I asked if he understood the implications of what he was saying.

“I’ve already talked with the Discipline Master (“Surveillant Général”), and he’s already given his consent. He’s a Catholic, you know!” That was the first time I was hearing that our discipline master, noted for his sarcastic remarks, and who did not miss an occasion to send a well-aimed kick into a student’s behind, was a Catholic. “If he’s a Catholic, why don’t you advise him to go to a priest and confess his sins of wickedness? That fellow is Hitler in disguise,” I said, recalling one instance when he gave me a humiliating knock on the head in front of Form 1 students. Imagine a Form 5 student being humiliated in front of ‘foxes’! For an answer, Emmanuel merely smiled and said he wasn’t that bad.

Holy Mass at school

Immediately after breakfast the following Sunday, Emmanuel took a taxi up to Small Soppo and before long, a white Renault 4 car drove into the yard. I was still wondering whether to attend the Mass or not. But then curiosity overcame my resistance and I walked to the classroom where a handful of people were already waiting. A hastily improvised altar, consisting of a teacher’s table, had been covered with a white sheet while another table at the corner held the chalice and other Mass accessories.

When I walked in, Emmanuel, who had already vested himself with an altar boy’s vestment, came to me and literally pulled me by the hand to meet the young priest. It was clear to me that he had already talked to him about me for Father Paul immediately came to meet me, a shy smile on his lips. “Oh, you’re Kenjo’s brother, aren’t you?” he asked in a low voice, a shy smile dancing at the corner of his lips. I said I was as we shook hands with each other. He immediately praised my brother’s writing skills, adding that he hoped I too would write as well as he did. I don’t remember what my response was, but I began to warm up to him. He didn’t seem that bad, after all.

That morning, we all sensed that Father Paul was someone who took Holy Mass seriously. His homily was well prepared and neatly typed out. To crown it all, he suddenly, and unexpectedly, switched from English to French and delivered the same homily in impeccable French. There we were, staring with open mouths as a young priest switched back and forth between English and French with such remarkable fluidity! And to think that we were always priding ourselves as being the only bilingual Cameroonians throughout the Republic! Father Paul’s language ability served as quite a lesson in humility to us.

No sooner was the Mass over than Father Paul’s language ability began to make the round of the school. Those who heard him repeated what they had heard to those who weren’t there, spicing their stories with elements of exaggeration. The result of this publicity was clearly visible the following Sunday when the room was packed full long before the young priest arrived. Those who came late crowded around the windows and door and the rest followed the Mass in the courtyard. At the front of the class, sat the “Surveillant Général” himself. He had obviously picked up rumours of the young priest’s performance of the previous Sunday and wanted to be present to see it for himself. And he wasn’t disappointed at all.

In fact, for the rest of the year, he never missed Mass and always cited the young priest as an example of a perfectly bilingual individual. He would always tell a student, who was fumbling in French or English, to go up to the young priest in Small Soppo for lessons in either French or English. Emmanuel, who was closer to the young priest than the rest of us, fed us with more of Father Paul’s linguistic exploits, telling everyone how easily he could also switch from Italian to Latin, or German, or Portuguese at a moment’s notice! Father Paul’s reputation soared to the sky among the teachers and students alike. Outstanding among his visible traits was his remarkable humility. He would smile shyly before making a remarkably profound point in simple straightforward English or French.

Father Paul becomes Bishop Paul

The following year, 1970, I gained admission into the Cameroon College of Arts, Science and Technology (CCAST), Bambili. I did not know what had become of Father Paul until one day I heard on radio that he had been appointed the first indigenous bishop of the newly created Diocese of Bamenda. I remember sharing that news with some of the students, who had been with me the year before in the Buea, and one of them graphically described his appointment as a log of wood falling before a man with a sharp ax!

On the day of his outdoor ordination in Bamenda, I was among the several thousands of lay faithful, clergy and curiosity-seekers, who thronged the location. Even though I was a little too far by the side to see what was going on, I felt the intensity of the occasion deeply. I remember the then Father Pius Awa, today the Bishop Emeritus of Buea, who acted as the Master of Ceremony, telling the excited crowd: “Na wuna bishop dis. From now, Bishop Julius Peeters he power for Bamenda don finish.” The shout of joy that rose from that assembled crowd must have been heard several dozens of miles away. I looked up and saw the newly ordained bishop on a chair, a mitre on his head and a crozier in his hand, looking really majestic.

Shortly after this ordination ceremony, the Cameroon government made a dramatic announcement: it had arrested Bishop Albert Ndongmo of Nkongsamba for treason, a term which became synonymous with a sure death sentence in the Ahidjo days. The then dreaded Jean Forchive, Ahidjo’s infamous torture-master, a man who boasted to the world that he would not hesitate to torture even his own mother, if she were to endanger state security, came on radio to rudely interrogate Bishop Ndongmo. The sentence of that trial shocked the world: Bishop Ndongmo was sentenced to death, a sentence that was later commuted to life imprisonment under pressure from the international community. Bishop Ndongmo was later ‘pardonned’ and forced into exile in Canada, where he ended his days on earth. Irony of fate, the man who tried, sentenced and exiled him became himself the object of a trial for treason. He too was sentenced to death, and chased off into exile. While Bishop Ndongmo is buried in his Cathedral in Nkongsamba, Ahidjo, his arch enemy, lies abandoned on foreign soil. How low the mighty do often fall!

Shortly after his ordination, the young Bishop Paul Verdzekov led a delegation of Cameroon’s bishops to Ahidjo on behalf of Bishop Ndongmo. It is not clear what they told the dreaded Ahidjo, nor what the latter’s reaction was, but it is of significant historical importance that it was a young man, a newly ordained bishop, who stood with courage before an unforgiving dictator to speak on behalf of a falsely accused colleague. It’s unfortunate that Father Paul passed on just when he was said to be working on a book in which he intended to denounce the Ndongmo trial as a sham and a travesty of justice. His biographer may reveal what his findings were to us.

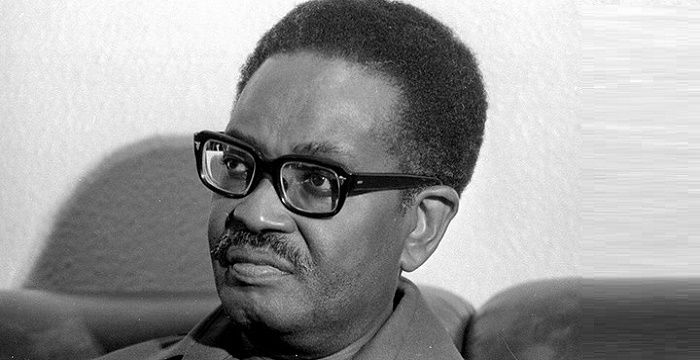

Bishop Paul and I

As I mentioned earlier, I did not have any particular relationship with Father Paul Verdzekov apart from one of a lay faithful, who happened to have had the privilege to meet him at close quarters from time to time. I remember meeting him on a number of occasions at Dr. Bernard Nsokika Fonlon’s residence in Yaoundé back in the 1970s when I was Dr. Fonlon’s student at the University of Yaoundé. I heard a lot about him from Dr. Fonlon, who was always very proud of his primary school pupil, who had risen to the rank of Archbishop of the Holy Roman Church. Father Paul was one of Doctor Fonlon’s primary school pupils back in the forties and Doctor Fonlon always had great words of praise for Father Paul’s intellectual ability.

When I came back home in the mid-eighties, after several years of studies abroad, writing, especially in newspapers, was already one of my intimate exercises. I wrote frequently and extensively, especially in English tabloids, notably in the English version of Cameroon Tribune. This was before President Biya began to loosen his iron grip on press freedom and grudgingly tolerate newspapers and magazines of differing political coloration.

In the late 1980’s, some Anglophone journalists launched a magazine entitled Cameroon Life and invited me onboard. It was only later that Father Paul Verdzekov admitted to me that he was an ardent reader of some of the things I wrote, especially in that magazine. I recall an interview I had in an issue of that magazine with one distributor of condoms in Cameroon. He was an American, who took much delight in marketing his product through our magazine. A few weeks later, I received a package from the Archdiocese of Bamenda with a letter from the Archbishop himself. Accompanying that letter was a book entitled The War Against Population by Jacqueline Kasun. It’s an enlightening study debunking the often held over-population myth, which abortionists and other population controllers use to justify their war on unborn babies. Father Paul’s aim in sending me a copy of that book was to let me see for myself the true facts about population control as against the false claims made by the condom seller in his interview.

I recall another article I wrote in another tabloid in which I urged the Yaoundé University authorities to rename the University of Yaoundé as “The Bernard Nsokika Fonlon University.” It appeared in a fairly obscure tabloid in Douala, whose publisher had been on my back for months to write for his paper. I remember sending a copy to Father Paul Verdzekov and, to my greatest surprise and delight, he sent me a handwritten letter, praising my contribution to journalism in Cameroon. I valued that letter so much that I carried it around with me for years, and I’m sure I can still find it among the jumble of boxes I have stashed in my garage.

More frequent meetings.

When Christian Cardinal Tumi invited me, in the late nineties, to join the team that was to revive the Catholic weekly, L’Effort camerounais, I received many words of greetings and praise from Father Paul. Whenever we met, he would always greet me with the words: “Martin, thank you very much for what you and your team are doing for the Catholic press.”

Later, when he became the Archbishop Emeritus, he came to Douala a little more frequently than before. I would often meet him in the Bishop’s House and we would talk at length about the press, the country and my work as the General Manager of the Catholic Media House, MACACOS. Then I would hear the usual refrain: “Martin, thank you for what you’re doing for the press and for the help you’re giving Cardinal Tumi.” Then he would tell me the latest book(s) he was reading. He was such an avid reader!

The last time we met, which was some months before his death, he was reading a book by the Holy Father, Benedict XVI. I forget what it was about but he was excited about it, smiling shyly before giving me a description of what the book was all about.

Father Paul, as I pen these few words of mine on you, I feel a sense of relief descending on me; not that long ago, I had been invaded by a feeling of uneasiness, which I knew would only disappear if I share my thoughts of you with others. It’s true that I did not know you that well but the few times we exchanged views on issues of civil or religious life, I left feeling truly enlightened.

I pray to you, Father Paul, because I know that you are in heaven, where people imbued, as you were, with goodness towards all, receive their rewards. When my own time runs out, I hope our Lord will also open the room for me in which you and the likes of Professor Fonlon, my friend Emmanuel Konglim, presently reside, exchanging notes on issues of importance to the world in which you now live. Father Paul Verdzekov, pray for me. Amen.