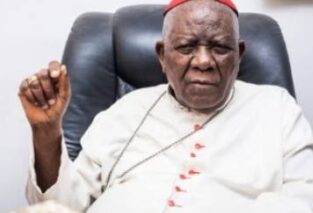

The University of Buea, in English-speaking Cameroon, prides itself as the only university, among the seven state-run universities in Cameroon, that allies itself more closely with the Anglo-Saxon university tradition. It therefore gives pride of place to contacts, in the form of seminars, workshops and conferences, with universities in the English-speaking world, in Europe, Africa and the Americas. One such contact was the (November 2008) conference entitled “Bridging the Atlantic”, which it jointly organized with two US-based universities: Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, and Purdue University in Indiana. The keynote address, reproduced below, was given by the Catholic Archbishop of Douala, His Eminence Christian Cardinal Tumi.

Ladies and Gentlemen:

I will like to thank the organizers of this International Conference on Caribbean and African Literatures for inviting me here today. I must admit that your invitation came as a surprise to me. Not being a student of literature, I was wondering what experts in that field could expect of me. But then, as I looked closely at the theme of your conference: “Bridging the Atlantic”, I began to see where I could say a word or two.

As we all know, Africa was, for centuries, linked to the Americas, in general, and to the Caribbean, in particular, by the infamous Middle Passage, that is, over four hundred years of the most brutal uprooting of Africans from Africa to the Americas, as slaves. Millions died on the way and those who made the cruel journey never came back to their homeland. These are historical facts that have been thoroughly documented and we are not here to evoke them for the sake of evoking them.

The challenge for you, literary men and women, I would imagine, is to reflect on how the outcome of this history is expressed in creative writing in the Caribbean and Africa. We find in the songs, rhymes, folklore, music and other forms of artistic expression of the Caribbean writers the vestiges of their African past. African cultures, as we all know, are very religious. As some of you, students who study the survival of African cultures in the Americas tell us, it is thanks to religion that African cultures have survived in the United States, in the Caribbean and in Latin America. Brazil is usually the most cited example where religious practices of the Yoruba people of Nigeria have survived in their purest form.

So when scholars meet, as you are meeting here today, to discuss ways of bridging the Atlantic, I would imagine you would be looking at those vestiges of African cultures that survived the brutality of the master’s whiplash in the plantations of the Caribbean and, in turn, examine what has come back to Africa from across the Atlantic. A bridge serves both ways; it enables people to go back and forth from one shore to the other, from one culture to another. African cultures are noted for their dynamism and elasticity, being able to absorb aspects of other cultures into theirs, thus creating new cultural hybrids in the process, which should also find expression in literary creativity.

You will be asking yourselves questions such as:

• What have we, who live on both sides of the Atlantic, in common?

• What bridges us?

• What is the nature of this bridge?

What unites us is spiritual. We all are spiritual and material because we are all human persons; and because we are all human persons on both sides of the Atlantic over which the bridge is built, we have similar qualities: we both reason and will. That is to say man’s nature obliges him to seek the truth, be it logical or ontological, scientific or theological. His intellect necessarily accepts the objectively true, no matter its origin, no matter from which end of the bridge it comes. Every truth is universal.

Because the Caribbean and the African are human beings, they both love the spiritually or the physically beautiful. They both, as writers, love what is literally beautiful. The Caribbean and the African are both endowed with faculties of being able to reason and to will.

On the stage of what is common to both, they have their different entrances and exits. What makes a Caribbean different from an African? They have the same essence, but distinct from one another. They have the same degree of being “which gives them a certain mutual similarity, but their essence has its own characteristics in each of them.” Their substance is the same and universal but their accidents situate and make them different.

The Caribbean and the African are mutually similar but individually different. This essential identity explains the similarity in what they do, say or write. Their mutual similarity, their essence, is the bridge between them.

But they are different. A Caribbean is not an African and neither is an African a Caribbean. The Caribbean has his way of life influenced by his history and geographical location on the map of the world. This makes the way he expresses his ideas accidentally different from the way the African writer does his. The substantially the same is said in accidentally different ways.

Ladies and Gentlemen, there has never been a time in human history when cultures have been fusing, mixing and blending as rapidly as it is happening these days. This is made all the easier by dizzying technological advances, especially in the field of information technology. These so-called “superhighways of information technology” bridge the Atlantic so easily.

I would imagine that in the course of your deliberations you’ll examine the challenges this poses to writers and critics of creative literature in Africa and the Caribbean. On what lane, along this “superhighway of information technology” is the African writer cruising? Is he on the slow lane, on the fast, or on any at all? On what lane is the Caribbean writer? Has his proximity to the United States of America, the source of much of these technological advances, given him a clear advantage over his African counterpart? I believe the answer is a resounding YES?

With such an advantage, how can he help his African counterpart on the slower lane to increase his speed so that both of them can cross this bridge over the Atlantic both ways with greater but cautious speed, picking up what is positive along the way from this new dispensation, but firmly rejecting the negative.

And the negative, there is a lot of it on this superhighway, particularly on the Internet. That is why I cannot end without sounding a word of caution, concerning the use of the Internet, in particular. His Holiness Pope John Paul II, one of the greatest communicators to have occupied the See of Saint Peter, strongly urged Christians to evangelize the Internet. It is a world that is still almost totally unregulated. It is as capable of the worst, as it is of the best. But, for the most part, we tend to go for the worst, characterized by unbridled violence, pornography, especially on children [paedophilia], promotion of hate literature, etc. So, conferences like this one, while rightfully lauding the advances of modern technology, should not fail to caution its users, especially the younger generation, of the dangers lurking in it.

One of the greatest difficulties creative writers in Africa have always faced is the lack of publishing houses. There is also the general lack of a reading culture in many places in Africa, notably Cameroon. The question that comes to mind is how a Cameroonian writer, for example, can survive in this world of instant communication and competition. Is it possible for him to publish his works on the web? If yes, for whom? If no, then how can he survive in such a highly competitive world as ours is today?

As you strive to bridge the Atlantic, never forget that, as creators of literary works, you also have the obligation to bridge the wide gap that separates our world into two: one inhabited by a handful of excessively rich and arrogant individuals, and the other by the majority of the downtrodden, the wretched of the earth. Whether it is in the Caribbean or in Africa, these two worlds stare us in the face, the one with arrogant glee, the other with tears and sobs of misery.

You, creators and critics of literary works also have the obligation to lay bridges of social peace and justice among peoples. African writers and writers of African descent everywhere in the world must promote the positive aspects of our people’s image, while not refraining from condemning the excesses of some of our leaders, who have gained unenviable notoriety for their brutality and their embezzlement of public funds. The message that should go from Africa to the Caribbean and from the Caribbean to Africa through your creative efforts should be one that defends the inalienable rights of our people to freedom, social justice, peace and dignity. We need as many bridges as there are human needs.

Once more, thank you for inviting me to your deliberations and may God continue to guide and bless your literary endeavours.

+Christian Cardinal Tumi,

Archbishop of Douala.