On the occasion of International Translation Day (September 30, 2024), a day dedicated to honouring the vital role of translators, interpreters, and other language professionals in promoting global communication and understanding, the Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters of Cameroon (APTIC) organised a seminar on “Translation as an Art Form.”

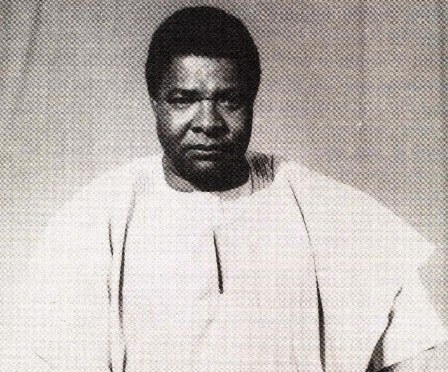

As I listened to the discussions on what it takes to be a good translator or interpreter, one figure came to mind and has since stayed with me: Professor Bernard Nsokika Fonlon. Peace to his soul! August 26, 2024, marked 38 years since he answered his Maker’s call and moved forward to receive his eternal reward.

Historical circumstances made him one of our country’s first translators and interpreters. He returned to Cameroon in the early 1960s, armed with impeccable university credentials, including a doctorate in philosophy, making him the first English-speaking Cameroonian to earn such a distinction. He arrived at a time when those fluent in both English and French were so few they could be counted on one hand. His linguistic prowess quickly caught the attention of the country’s first president, Ahmadou Ahidjo. Before long, Fonlon was serving as his translator and interpreter, and it was rare to see the president without Fonlon standing close by, within whispering distance.

Unlike many of today’s graduates from foreign schools of translation and interpretation, or from the now burgeoning local institutions—most notably the Advanced School of Translation and Interpretation (ASTI) at the University of Buea—Fonlon’s credentials in translation and interpretation rested solely on his mastery of Cameroon’s two official languages: English and French.

It was no surprise, then, that when it came time to translate the national anthem, inherited from the French colonial past, Fonlon was assigned the task. However, instead of translating the original, he chose to write a completely different version—an act that has sparked much controversy in academic circles. He told those of us who sat at his feet at the then-lone University of Yaounde in the 1970s that he had no qualms about discarding the original French text. Among its many incongruities, he said, it celebrated Cameroon’s emergence from the ashes of “barbarie” and “sauvagerie.” He found it impossible, he said, to put such words into the mouths of Anglophones. This led him to create an entirely new anthem in English—an audacious move that has puzzled many Cameroonian intellectuals, including scholars like Professor Thomas Théophile Nug Bissohong of the University of Douala, who has a publication about it.[1] In fact, there was a recent surge of seminars organised by government ministers, notably the Minister of Higher Education, specifically addressing what to do about the two national anthems coexisting in our country. The answer is still awaited.

Despite his well-honed intellectual credentials, Fonlon never spent a day in a translation class or an interpretation booth—at least, not to my knowledge. This likely explains why he overlooked one of the key principles of translation: fidelity to the source text. By discarding the original French text he was tasked with translating and writing a completely new one, Fonlon violated the fundamental requirement of faithfulness expected of translators. In doing so, he deprived his client—the Cameroonian government—of a translation that should have reflected the original text as closely as possible. A translator or interpreter must always strive to balance fidelity to the original message with the freedom to adapt the text or speech to the nuances of the target language.

Translators and interpreters serve as a bridge between cultures, a role that demands not just linguistic fluency—of which Fonlon had plenty—but also a deep understanding and appreciation of the cultural context shaping the text being translated, something he chose to overlook. A key artistic challenge in translation is preserving the original author’s or speaker’s unique voice, style, and tone. Whether translating literature, poetry, or live interpreting a speech, the translator or interpreter needs to maintain the tone—be it formal, casual, humorous, or poetic—so that the target audience experiences the same emotional or intellectual effect as the original. This demands a sensitivity to how language conveys feelings and intentions, which Fonlon either did not know or chose to ignore.

In conclusion, the translator’s or interpreter’s ultimate goal is to remain as faithful to the original as possible, even if their personality and voice inevitably shape the final product. In Fonlon’s case, however, his personality and convictions completely overpowered the original document, replacing it with one of his artistic creations. I only hope no one sent him a cheque for his efforts—his betrayal of his client’s trust surely deserved no reward!

[1] Thomas Théophile Nug Bissohong, L’hymne national du Cameroun: un poème-chant à décolonialiser et à réécrire: relectures critiques et perspectives. Editions CLE, Yaoundé, 2009.