(Revised and reproduced from The Herald, N° 022, Wednesday, January 13-20, 1993, 9.13).

One Saturday morning, my wife and I were returning from the market when she spotted a vehicle from the American Consulate in Douala in front of our Francophone neighbour’s gate. I remember us wondering what business Americans could possibly have with that obnoxious woman who was always spoiling for a fight and quarrelling at the drop of a hat. Imagine her loudly grumbling because she said we were always laughing in our house! What did humanity ever do wrong to her that she should bear it such a deep grudge? I always wondered.

I had hardly bolted our gate when the bell rang. I opened the door and was met by a smiling, white-haired, middle-aged white man, with a greying goatee and side-burns, in white jean trousers, short-sleeved shirt and suede shoes, with a bag casually slung around his shoulder. Beside him stood a young, medium height, black man in a brownish shirt, dark trousers and tennis shoes. It was he my wife, Maika, had recognised as a driver from the American Consulate.

I recall exchanging the traditional greetings with them and then wondering of what assistance I could be to them.

“I am Richard Bjornson, sent by Steven Arnold to look for Martin Jumbam”. I jumped with joy for, even though I had never had the occasion to talk to Professor Bjornson before, I knew much about him.

“Professor Bjornson, very pleased to meet you, Sir”, I said as we shook hands.

“Just call me Richard or Dick, if you like; no Professor business here, all right Martin?” he asked, a broad smile opening up on his face. I said that was fine with me.

Colonial Critic?

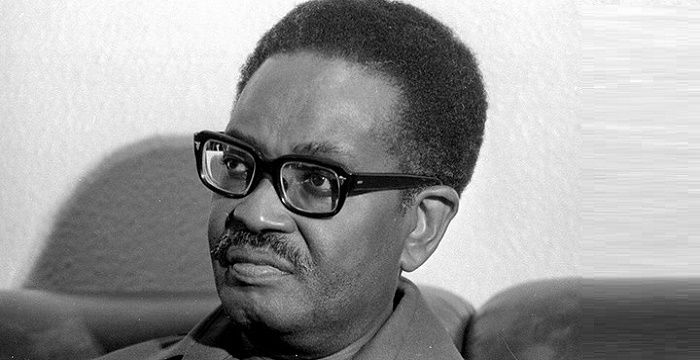

I first met Richard at the African Literature Association Conference in Gainesville, Florida, in 1980, where he was on a panel dedicated to Cameroon Literature. He had presented a paper on Francis Bebey’s literary works. Bebey himself happened to be present, although Richard confessed he had not known he was there until he stood up to react to his paper.

Francis Bebey had been invited to give a musical performance alongside two griots from Senegal. Griots were then very much in demand in North America following the well-publicised role they played in Alex Haley’s best seller, Roots.

Bebey’s reaction to Richard’s paper was surprisingly violent. I recall him angrily and sarcastically referring to Richard as a colonial critic who knew nothing about the environment informing the work of art he was criticising.

As usual, that reaction sparked off much heated debate over the role of the non-African critic in assessing creative works from Africa. That Bebey-Bjornson confrontation made its home in my mind and thereafter, whenever I read anything either by Bebey or Richard, it always bubbled to the surface.

In a way, therefore, that conference in Florida did open Richard’s works to me and I came to read much of what he wrote on African, and especially, Cameroonian literature. He was also an excellent translator, a profession I had also made mine, and I always marvelled at his indisputable command of both English and French. So, Richard was a teacher to me in many ways, although it was not until he came to my house that we met in person for the first time.

Prestigious review

Even though I never had the chance to talk to him in Florida, or at any other time thereafter, Steve Arnold, my friend and professor, not himself a stranger to Cameroon, or to Cameroonian literature, always talked to me about the exciting things Richard was doing for our literature. It was he who informed me of Richard’s appointment as editor of that prestigious review, Research in African Literature (RAL). He took over from the man who had founded it and run it for well over twenty years, Professor Bernth Lindfors, another giant of African literary studies.

As we sat in my living room that Saturday morning, sipping a cool drink and discussing literature and politics, Richard said he was in Cameroon to award the first Fonlon-Nichols Prize to two Cameroonian writers, Rene Philombe and Mongo Beti. He (Richard) was one of the founders of that award. He said Steve Arnold had already given Beti’s award to him in France and that he was here to give Philombe’s to him in person.

My wife, Maika, insisted he stay for lunch, but he expressed his regrets, saying he had to leave for Yaounde that same afternoon and did not want to miss his flight. He promised to come over for lunch or dinner upon his return from Yaounde.

Before leaving, he gave me a copy of Research in African Literature, Vol. 22, No. 4, Winter 1991, containing an excellent article by Dr Ambroise Kom relating the torments the organisers of Beti’s recent visit to Cameroon in over thirty years, and Beti himself, had been subjected to during that visit. Richard himself had translated the article in question from the French original.

Chicken-parlour encounter

When he returned from Yaounde, he gave me a call and we met in a friend’s chicken-parlour in Akwa. Maika was with me and Richard came along with Ms. Jeanne Dingome, a fluent, American-trained, well-travelled and well-read Cameroonian lady, who was then at the head of the English Department at the University of Douala. Ms. Dingome was also a member of the African Literature Association and so we had a lot in common to talk about.

Prior to Richard’s departure from Cameroon, we agreed that I would send him money in exchange for a copy of his recent book on Cameroonian literature, The African Quest for Freedom and Identity: Cameroonian Writing and the National Experience (1991). I did send the cheque as promised but, unfortunately, the book never arrived before his death.

Tremendous Changes

Richard was in Cameroon at a time of incredible political mutations in the country. I remember him expressing great surprise that things had evolved to the extent that the Cameroon Radio and Television Corporation (CRTV) could dare cover the Fonlon/Nicholas Prize Award to a man like Philombe, who had never hidden his hostility towards the regime in power. He was also amazed at the virulence of the private press towards the governing prince. Such a thing, he said, was unthinkable when he was a Fulbright Scholar, teaching with Dr. Fonlon at the University of Yaounde a decade or so earlier. His only fear was that the dynamic private press might fall prey to the facile temptation of indulging in indiscriminate mud-slinging and rampant name-calling that could, in the long run, stifle investigative analysis of facts.

Encounter with the literati

He was pleased that the CRTV had also aired the round-table discussion he held in Yaounde with some well-known Cameroonian men and women of letters, although he was sad he never had the chance to watch the televised version himself. He had touching words of praise for the participants at that forum, notably Dr. Bole Butake (perhaps the only intellectual in this country to have openly spat on an invitation from President Biya to share in the loot of the nation). He also thought highly of Dr. Godfrey Tangwa, a philosophy lecturer and a noted play-actor who had gained much notoriety as an uncompromisingly virulent columnist, whom someone graphically described as an irritating “jigger in the toe of the Biya regime”. He also had good things to say about Dr. Eyoh Ndumbe, a promising playwright, Dr. Lyonga Nalova, a promising critic, and Lecturer of African literature, and Dr. Ambroise Kom, whose name rings with much credibility in international literary circles. He too was one of those intellectuals that were not on the good books of the Biya regime.

Death halts future projects

Since he had not had the chance to watch that TV programme himself, Richard wondered if I could get him a copy of the tape. I said I would talk to CRTV Yaounde and arrange to purchase a copy of the said tape. I feel sad that I never got round to it. When I picked up a copy of one of our newspapers and read Dr. Ambroise Kom’s announcement of Richard’s death, my first reaction was one of profound shock, especially as he and I were already discussing some exciting future projects together. It was not until Ms. Jeanne Dingome rang, that it finally dawned on me that Richard was truly no more. How sad!

May his path to eternity be a smooth one!