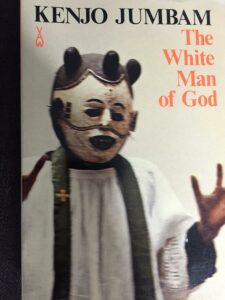

Mention the name Kenjo Jumbam to most Anglophone Cameroonians, who came of secondary school age in the 80s and 90s, and the reaction would almost always be: “Oh, he is the author of The White Man of God, isn’t he?” And many would then tell you how much they enjoyed reading that book in their secondary school days. In addition to the White Man of God, Kenjo also penned other books such as The White Man of Cattle and Lukong and the Leopard, that also became required reading material in some schools.

It is worth mentioning that long before our Ministry of National Education ever gave a head-nod to his books, the said books were already in use in secondary schools in Northern Nigeria and in East Africa (Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda). In fact, the Ministry of Education of Tanzania invited him to give talks and workshops on creative writing to young Tanzanians in Dar Es Salaam, the then Tanzanian political capital.

The Englishman who made it happen.

When he was in Dar Es Salaam, he crossed paths with a young British official serving at the British High Commission in Tanzania, an encounter that would prove decisive in convincing Cameroonian educational authorities to not ignore a writer of great worth in their midst. This came a few years later, when the said British official was transferred to the British Embassy in Yaounde from where he also played the role of adviser in the Ministry of National Education in matters relating to the teaching and learning of English.

As soon as he arrived in Cameroon, the Englishman contacted Kenjo and was stunned to learn that none of his books was being studied in Cameroonian secondary schools. He immediately asked the officials of the Ministry of National Education, even meeting the incumbent minister, for an answer as to why a prominent writer of Kenjo’s stature was ignored in his own country. As it so often happens in our land, we only begin to acknowledge the jewel under our feet when, and if, a foreigner, especially a white one, points it out to us.

Give us “choko”!

Before Kenjo was made aware of the Englishman’s intervention, two officials from the Ministry of National Education, rushed to his office to ask how much he was prepared to give them so they would recommend his books for use in our secondary schools. They told him, facts in hand, that it was a truly lucrative market, and that they would help him grab a share of it, if only he would cooperate with them. The usual Cameroonian “choko” business!

Kenjo informed them that his books were being used in secondary schools in Northern Nigeria and in Eastern Africa and that he never went to any of those countries to ask them to include his books on their reading lists. He told them that he was receiving his royalties from those countries on a regular basis through his publishers, the London-based Heinemann Books. They left disappointed, loudly regretting that he was about to lose a juicy ‘soya’ at the end of the stick they were dangling before him. That was the famous Cameroonian “You-rub-my-back, I-rub-your-back” formula! Shortly thereafter, the Ministry of National Education announced the list of books for secondary education for the following academic year, and Kenjo’s books were among. That is how his books meandered their way through the dark, nebulous and often mysterious labyrinths of book selections for secondary schools that then prevailed in our country.

PRESBOOK swings into action

You would be excused for thinking that a man whose books were part and parcel of our secondary school curriculum would reap much profit for his sweat – the legendary ‘soya’ the education officials so temptingly thrust under his nose. Think again. Even though his books became standard reading in our schools, the expected financial reward, in terms of book royalties, did not follow, and here is why.

No sooner had the ministerial order been approved than the expected windfall (the ‘soya’) became a curse rather than a source of joy. That was because a formidable, financially-well-endowed bookseller, called PRESBOOK, the property of the Presbyterian Church of Cameroon, swung into action. Overnight, it pounced on Kenjo’s books, crossed the border to neighbouring Nigeria where it churned out thousands of illegal copies with which it flooded the Cameroonian book market. For the many years Kenjo’s books were used in Cameroonian secondary schools, the predicted juicy ‘soya’ was dangling from a stick in the wrong hands – those of a church entity!

Some years later, Kenjo’s publishers, Heinemann Books, took legal action against PRESBOOK, unwisely filing their lawsuit in Limbe of all places, which happens to be PRESBOOK’s backyard. Needless to say that the case dragged on for years with interminable interruptions and adjournments for one reason or another. Kenjo, who was then retired, poor, broke and in ill-health, made endless trips from his village of Nkar to Limbe. He finally died without ever touching a single franc of what was rightly the reward for his intellectual labours. It was not surprising that the case was finally thrown out of court. Greed for money had held sway over the word of God!

Not Kenjo alone

Later, when his books were no longer on the curriculum, PRESBOOK inserted a list of books in a local newspaper, inviting the writers concerned to collect them as a matter of urgency, failure to do so within a month of publication of the said list, PRESBOOK would reserve the right to dispose of them as it deemed fit. Kenjo’s books were among them. The profit-juice from the illegal sale of his books had run dry since the books were no longer in use, and the profiteer’s warehouse had to be cleared so that the current books, most probably also pirated and plagiarised, could find room. That is the fate of writers in Cameroon!

If the theft of Kenjo Jumbam’s literary rights has so far been the only one that has, to my knowledge, been heard in a court of law, it does not mean that many other Cameroonian writers, whose books are required reading in our schools, have not also been swindled out of their copyrights. The question now is, what are copyright enforcers doing to protect our writers from being swallowed by plagiarism-sharks and other book predators and pirates? The answer is blowing in the wind!