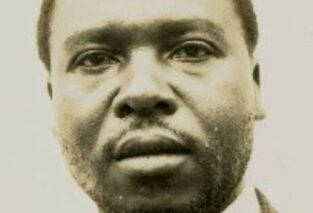

On the night of March 8, 2007, English-speaking Cameroon lost one of its most articulate but eccentric, erratic and choleric writers, Bate Besong, more commonly known as BB. He died with three friends of his in a car accident along the Douala-Yaoundé highway. Five years later, friends and foes alike continue to celebrate the life of a man of letters, whom some acclaim as our own ‘Soyinka’. Here is what I remember about him.

Usually, when my phone rings and I see my friend Francis Wache’s name and number flashing on and off, I always answer with “Hi, Francis, what’s up?” and expect the usual answer of “Oh, not much, I just wanted to tell you about ….”, and the conversation would usually take a lighthearted tone as we go from one topic to another. It was not the same thing on that morning of March 8, 2007. His response was simply, “have you heard about BB?” His emotion-drenched voice left me in no doubt that something tragic had happened; and that was indeed the case.

An unnecessary accident.

“What’s wrong with him?” I recall asking. “BB is now history. He died last night along the Douala-Yaoundé highway”. I recall shouting “Oh, no! That’s not possible! What happened?” Francis then gave more details of the accident. He was not alone with the driver in the car. His close friend, Dr. Hilarious Ngwa Ambe, whom I had never met before, but had heard the two were inseparable, and Kwasen Gwangwa’a, whom I had never met either, but whose name was familiar to anyone who watched Cameroon television, since he was involved in artistic production on television.

“What a monumental loss!” was all I could say. Then details of the accident emerged: the rickety state of the car they were in, the ungodly hour of the night they chose for the journey, and questions about their state of sobriety – all of them having spent a good part of that day and well into the evening celebrating the successfully launching of BB’s latest publication, a book with a typical BB title, Disgrace.

Those present at that event talked of how magnanimous Bacchus, the god of alcohol, was that day, generously oiling the lips, throats and minds of participants, sending many of them swaying from side to side and reeling with much laughter. That BB and his friends could have taken to the road after such an evening seemed difficult to believe.

Feelings tinged with suspicion

BB and I had a strange literary ‘feeling’ for each other. I am one of those reasonably well-educated Anglophones who never understood, nor greatly admired BB’s literary endeavours. When one of his great admirers, Douglas Achingale, recently recalled how a young university student had asked BB to go back to school to learn to write simply, I nodded in approval. I abhor literary obscurantism, which seems to have been BB’s literary headgear. The few things I read, or tried to read from him – be they articles in the papers or some of his books – always sounded either too opaque or too pompous for my liking; and I would always end up tossing them aside.

However, when I read rave reviews of his literary stamina from folks I hold in high esteem – Mwalimu George Ngwane, Dr. Joyce Ashuntangntang, Doug Achingale, among many others, I always shake my head in wonder. What use is literature if it is not clearly understood by the ordinary man or woman? I wonder. And to me, BB was not for the ordinary mind. His eccentric behaviour characterized by a tendency to flare up in a mad rage against anyone who would not praise his work to the sky, tended to alienate me from him and from his literary production.

Ngong and Namundo

The quarrel I never had with BB – at least, not directly – was over a column I ran in Cameroon Life Magazine entitled simply “Ngong and Namundo”. Ngong was an innocent boy from upcountry, who fell head over heels in love with a beautiful girl from Bakweri land called Namundo. It turned out to be a stormy relationship, like many relationships among young people the world over.

To BB and a number of intellectuals in Buea, however, Ngong was simply the archetype of the domineering northwest region of Cameroon, dominating and subjugating the southwest region, which it considered a mere woman to be used for its sexual pleasure. My friend Francis Wache, who was then the Editor-in-Chief of Cameroon Life Magazine, played the firefighter, dousing with little success BB’s rage over what he considered my unacceptable arrogance.

Matters came to a head when I thought that Ngong and Namundo had quarreled with each other long enough to seal their union in the robes of sacred matrimony in an episode entitled “Ngong and Namundo: No Divorce”. I pitied Francis who tried, in vain, to assuage BB’s anger by pointing to the unflattering depiction of Ngong, who embodied stinginess, wore socks with holes in them and had to be very strongly reminded that it was all right, from time to time, to wear something new. The man’s idea of a night out in town was to take his wife-to-be to eat ‘soya’ in New Bell, for fear of spending money in a better restaurant in Akwa. Even with that, the rage against the column continued unabated, skillfully stoked by none other than BB himself.

He stormed Francis’ office each time the magazine appeared with the column still in it. To him, and others of like mind, I was arrogantly celebrating and imposing a mindset of dominance typical of people from my region of the country, and should therefore be expelled from the magazine. Irony of ironies, a writer of BB’s stature, who would not tolerate any comment that was not pouring syrup on his work, inexplicably undertook an intensive crusade to have a column banned from a magazine, for reasons other than literary.

Political sycophants

At the same time as BB and a few others in Buea were assaulting my column, political sycophants and stooges of all shade and colour also entered the ring. Understandably, some of my political characters had names that had an uncanny resemblance to real life politicians at the time in our country. There were, for example, Benjimanou Itoesu, Ifrima Inini, Firancir Niwain, Yoanir Nubi Ngah and Laviran Fanko Shung. Even though I had my left hand on the Bible and my right hand up in the air, pleading my innocence, no one believed that I was not out to make fun of them.

The last name mentioned above – Laviran Fanko Shung — sounded very much like someone from my village who then held an important position in our country. His enemies, and he seemed to have tons of them, nearly hoisted me on a pedestal as their ‘hero’, who had aptly dressed their political enemy in the dark colours he deserved. To his supporters, however, I was a mere subversive element whose writings, if allowed to continue, would drown their hero’s chances of retaining his post. Petition writers had a field day, flooding the ruling prince’s secretariat with one incendiary letter of denunciation after another. I was painted as a cunning rabble-rouser, who took delight in whipping up dangerous sentiments that could consume, not only their hero, but also the political establishment as a whole. However, the fact that the ruling prince unceremoniously ejected their hero from his shaky seat proved that the petition writers had missed their mark.

So, I was being kicked from the intellectual left, under BB, and from the political right, by political sycophants in search of free drink and food; all this over an innocent column in a magazine.

Reconciliation

It must, however, be said that for the time this literary and political row raged on, I had no open confrontation with either BB, or anyone else in the intellectual circle in Buea. Whatever objection they had – and they seemed to have a lot to object to – always filtered to me through Francis, the firefighter. Through him, I could take the pulse of the literary climate in Buea whenever “Ngong and Namundo” appeared. When it looked likely that emotions could spill out in the streets, I steered clear of Buea; but when reason took over from emotion, I would then drive up for a feel of the cool Buea air and the taste of a heavily-spiced porcupine leg in one of the side-road restaurants.

Some years later, long after “Ngong and Namundo” had become history, having gone down with Cameroon Life Magazine, that wonderful tool of communication which Anglophones created and which one of them decided to kill by embezzling our funds – the said Anglophone now shamelessly championing the cause of the ‘oppressed Anglophone’ from the safety and anonymity of one of Uncle Sam’s cities – what a joke! Yes, after all those years, BB and I shook hands over a well-chilled bottle of ‘jobajo’ in a drinking spot in Buea, and silently decided to bury the hatchet of a war that was never openly declared, our friend Francis, as always, officiating. I had all along known what BB’s views were because he was openly hostile to that column, and did not hide his hostility from Francis. He knew Francis would, of course, relay his thoughts to me, and he knew my own views that went to him through the same safe conduit.

Presbook and book piracy

How did the “reconciliation” come about? I have the Presbyterian printing press, commonly known as ‘Presbook’, to thank for it. ‘Presbook’ is the commercial arm of the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon. Unfortunately, it has specialized in pirating writers’ works. Once a book is on the school curriculum in this country, chances are that Presbook would pounce on it, rush off to Nigeria, and reproduce the book for sale, completely ignoring the author’s rights.

Lest I be accused of blasphemy, let me say that my brother, Kenjo Jumbam, spent the last years of his life on earth pursuing Presbook in a Limbe court for piracy. His books, which were on the reading lists of schools in Cameroon for several years, fell into the hands of a redoubtable pirate called, Presbook, which shamelessly reproduced them in neighbouring Nigeria, in complete defiance of copyright rules.

My brother and his publishers, Heinemann Educational Books, were left in the lurch. Heinemann’s representative in Cameroon, a certain gentleman called Nkwanyou, and my brother, jointly brought legal charges against Presbook. Unfortunately, as sad reality in our land shows, such court cases always end up in the pockets of the party with a more solid financial muscle; in this case, Presbook. A poor, retired, ailing writer, like my brother, who was barely surviving on his pension, stood not the least chance of a fair hearing.

Only the other day, Presbook put out a statement in the papers asking certain authors, among whom was Kenjo Jumbam, to come for the unsold copies of their books before a certain date, beyond which they would dispose of them as they deem fit. Now that Kenjo Jumbam’s books are no longer in the school curriculum, Presbook no longer has any use for them. What they did not dare tell the world is that they unlawfully reprinted my brother’s books and sold them for their own benefit, in total defiance of laws governing copyright anywhere in the world.

Joint mission to the Presbyterian Moderator

When my brother finally passed on with the case against Presbook still unresolved, I thought I would revive it by going to the top echelon of the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon. I discussed my thoughts with Francis and we decided to visit the Most Reverend Dr. Nyansako Ni Nku, whom Francis knew as a sedate, sober and fatherly man. I had heard about him but had never met him before. Our reasoning was that the preaching ministry of the Church, which the Reverend Moderator led, was probably not aware of the unethical business practices of its commercial arm. Artistic piracy definitely violates the very principle of justice and equity, which the Presbyterian Church, like any other church worth the name, stands for, or should stand for.

“Why not invite BB to come along with us?” Francis suggested. “You know how firm he can stand in matters of that nature.” I thought that was a cool idea and I asked Francis for his phone number. When he picked up the phone and I called my name, there was a slight pause as if he was running similar names through his mind. Then he burst out in his usual loud laugh, stuttering slightly as he greeted me and inquired about life in Douala. He sounded surprised and genuinely pleased by my call.

When he heard the reason for my call, he burst out in unprintable curses against book pirates, he himself, as a writer, a victim of the same foul play by book pirates. He said I only needed to tell him when I thought we could visit the reverend gentleman and he would be in the delegation. When the day came, he was not only in the delegation, he was in the lead, excited as always, saying what a sad fate was that of writers in our country.

Unfortunately, the Reverend Moderator was not home when the BB-led delegation arrived. His gentle and courteous wife informed us that her husband had traveled out of the country. We did not reveal the reason for our visit and she did not ask; so we accepted the crunchy “chin-chin” she offered – I nearly asked for a second serving – which we gratefully watered down with some chilled drinks, and then bade her goodbye.

Lord, be merciful to him!

There was no return visit but that encounter with BB pumped new life into what had hitherto been a rather chilly and moribund relationship. We spoke at length about the evil of piracy in Cameroon and lamented that an organization, like Presbook, a church property, would be in the lead of book pirates. We loudly wondered where that church drew the line between biblical teaching on justice and equity that so openly clashed with unacceptable commercial practices.

I recall running into BB again a few times thereafter. We shared a few jokes, but never about our writing, preferring to talk politics, a safe topic on which to vent our bile on corrupt government officials. That was when you would hear BB blare out insults against the political or academic establishments, with words like ‘iguanas’, ‘Mephistophelean nincompoops’ dropping from his lips with remarkable fluidity. It is sad that he could have exited from this world in such a tragic manner. May his feet be wrapped in divine fur!